By Ogova Ondego

When I first visited Zimbabwe on August 26, 2005 to attend the Zimbabwe International Film Festival as facilitator of a workshop for young film journalists and critics and to speak on Nigeria’s Nollywood home-video (straight-to-video) film phenomenon, I was apprehensive and curious as to what I would find in this country that has been so much bashed by western media. And to go to Zimbabwe, I had had to cancel another engagement in Italy. So that was how important the visit was to me.

When I first visited Zimbabwe on August 26, 2005 to attend the Zimbabwe International Film Festival as facilitator of a workshop for young film journalists and critics and to speak on Nigeria’s Nollywood home-video (straight-to-video) film phenomenon, I was apprehensive and curious as to what I would find in this country that has been so much bashed by western media. And to go to Zimbabwe, I had had to cancel another engagement in Italy. So that was how important the visit was to me.

What I discovered in the creative, intellectual and cultural sector of Zimbabwe blew me away: Zimbabwe is teeming with talent despite the economic and political problems plaguing her! The festival opened with Haitian Raoul Peck’s Sometimes in April film on the 1994 Rwandan Genocide, before giving the night away to a free open-air concert featuring female urban groove artists Prudence Katomeni-Mbofana, Sharon Manyika, and Duduzile Tracy Manhenga & Color Blu at the upmarket Avondale Shopping Centre in the heart of Harare. From then on, it was a fast-paced programme of workshops and film screenings at 7Arts, Vistarama and Elite (Avondale), Alliance Francaise and ZGS/Goethe Zentrum in Harare city, Young Africa (Chitungwiza) and Amakhosi, Alliance Francaise and National Gallery in Bulawayo.

Film Forum workshops were mainly at Zimbabwe International Film Festival Trust offices, Alliance Francaise and Amakhosi. Children, too, had their own fun for two days in the National Gallery Garden. With Zimbabwe Calabash (a special category for films either written, directed, produced or starring Zimbabweans) the festival screened an impressive array of international films from USA, UK, Spain, Japan, Italy, Sweden, Belgium, France, Cuba, Brazil, Egypt, India, Burkina Faso, The Netherlands, Switzerland, China, South Africa, Germany, Rwanda, Poland, Canada, Czech Republic, Norway, Greece, Nigeria, Mozambique, Congo-Kinshasa, Israel, and Russia. ZIFF also went a step further to give awards to Best African Costume, Best Picture, Best Actor/Actress in a Leading Role, Best Screenplay, Youth Art Attack, Zimbabwe Film Service Award, Short Film Project, and Zimbabwe Calabash besides the ubiquitous Best Documentary, Best Director, Best Shot Film, and Audience Choice. This put ZIFF ahead of most film festivals in Africa as it appeared to recognise professionalism not associated with African “festival films”. But Zimbabwe is not just about film, film and more film. Perhaps the greatest talent lies in the music, literature and art of this southern African nation whose name may have changed from Southern Rhodesia to Zimbabwe but its capital still bears European names for locations and landmarks: Avondale, Greendale, Rhodesville, Prince Edward.

Film Forum workshops were mainly at Zimbabwe International Film Festival Trust offices, Alliance Francaise and Amakhosi. Children, too, had their own fun for two days in the National Gallery Garden. With Zimbabwe Calabash (a special category for films either written, directed, produced or starring Zimbabweans) the festival screened an impressive array of international films from USA, UK, Spain, Japan, Italy, Sweden, Belgium, France, Cuba, Brazil, Egypt, India, Burkina Faso, The Netherlands, Switzerland, China, South Africa, Germany, Rwanda, Poland, Canada, Czech Republic, Norway, Greece, Nigeria, Mozambique, Congo-Kinshasa, Israel, and Russia. ZIFF also went a step further to give awards to Best African Costume, Best Picture, Best Actor/Actress in a Leading Role, Best Screenplay, Youth Art Attack, Zimbabwe Film Service Award, Short Film Project, and Zimbabwe Calabash besides the ubiquitous Best Documentary, Best Director, Best Shot Film, and Audience Choice. This put ZIFF ahead of most film festivals in Africa as it appeared to recognise professionalism not associated with African “festival films”. But Zimbabwe is not just about film, film and more film. Perhaps the greatest talent lies in the music, literature and art of this southern African nation whose name may have changed from Southern Rhodesia to Zimbabwe but its capital still bears European names for locations and landmarks: Avondale, Greendale, Rhodesville, Prince Edward.

Upon arriving at Harare International Airport, I was greeted with the hostility I have never witnessed anywhere. The unsmiling immigration officer who was to serve me looked at my passport and asked, “What’s your profession?” “Journalist”, I answered. And he almost jumped out of his skin. Instead he stood from his chair and kept away for about 10 minutes. Upon returning he asked, “Do you have permission to be in Zimbabwe?”

Upon arriving at Harare International Airport, I was greeted with the hostility I have never witnessed anywhere. The unsmiling immigration officer who was to serve me looked at my passport and asked, “What’s your profession?” “Journalist”, I answered. And he almost jumped out of his skin. Instead he stood from his chair and kept away for about 10 minutes. Upon returning he asked, “Do you have permission to be in Zimbabwe?”

I said yes and he demanded my accreditation but I told him my hosts had the papers ready.

“Are they here to meet you?” I answered in the affirmative and he ordered me to follow him to the visitor reception area where we met Isabel Manuel waiting for me. She gave the man a letter from the government permitting me to be in Zimbabwe and he growled that he was about to put me back on the plane to Nairobi.

To cut the long story short, he gave me one day to seek accreditation or be deported. I was taken to my hotel where my passport was photocopied and told I should settle my bills in hard currency, being a foreigner.

It was already 3.20 pm on Friday and I still had to seek an extension of my stay in Zimbabwe till Monday to get accredited. After being thrown from one office to another, a senior officer at the immigration department extended my stay to Monday on condition that “You will not work as a journalist. What we are doing is to simply give you more time to get accredited on Monday.” Come Monday, my accreditation was done in 15 minutes after my hosts pleaded with the Media Council not to charge me the press accreditation fee of US$500 and application fee of US$100 saying I was not in Zimbabwe as a journalist but as a workshop facilitator. They conceded and demanded that I not work as a journalist. I then had to return to the Immigration Department to have my stay extended to September 5. It was done but I was again warned against operating as a journalist though I had been accredited as one in this country of super millionaires where beer costs Z$50000, a meal of rice and chips Z$100000, breakfast at Harare Sheraton Z$370000, and entry fee to Chiwoniso Maraire’s concert at Mokador Hotel Z$60000.

I also discovered that the most economical way to travel in Harare is by the well organised, efficient but fewer City Cab taxis. These cabs are linked by telephone and charge the least, standard and pocket-friendly fares. The driver cannot just look at you and charge you anything as happened to me when I used a taxi from Avondale shopping centre to the Sheraton and also from The Sheraton to Crowne Plaza Hotel. The two hotels are too close but I paid through the nose for the services and quickly learnt that I should keep to City Cab while in Harare!

In almost every direction I looked, I was greeted with messages like, “All visa applications are to be made in foreign currency” and “Please be advised that it is a requirement that non-residents pay accommodation or hotel bills in foreign currency (cash, credit cards),” and “Money exchanged at a commercial bank in Zimbabwe dollars will not be accepted.”

I just could not understand why any one would dislike their own currency so much that they do not accept it as a mode of payment.

Being Kenyan, I was convinced they would accept my Shillings as I am neither European nor American to pay for services in Euros and American Dollars.

So did they accept my shillings? That is a story for another day!

Unlike other countries where I am usually greeted with, “Welcome to our country, we hope you will like it here and we always welcome writers with open arms” whenever they learn I am a journalist, Zimbabwean authorities appeared to loathe any one whose passport declares their profession as JOURNALIST. I was told that before issuing permission to ZIFF to bring me into Zimbabwe as a resource person, the government officials charged with the responsibility had had to closely monitor ArtMatters.Info to see what kind of stories we wrote about Zimbabwe and if my entry into Zimbabwe was not a decoy to disguise my real intention: giving negative publicity to Comrade Bob Mugabe’s illustrious leadership.

But Zimbabwe is not just about film, hyper inflation, lack of fuel and craving for American dollars, European Euros and British Pounds. I was very interested in meeting artists and finding out how they are faring in the heart of the storm that is Zimbabwe. Despite the biting lack of fuel unless one has hard currency with which to pay for fuel, many artists still made it to the venues where we were to meet. Tawanda Gunda Mupengo is a screen writer and film director whose two films, Tanyaradzwa, Masiiwa: a love for life, were launched during the Zimbabwe International Film Festival. Mupengo says he has been inspired by the Shona oral tradition. Painting a Scene, a 15-minute film he wrote and directed at the now defunct UNESCO, Zimbabwe Film and Video School about a girl torn between a rich and a poor lover, won an award in 2000 while Vengeance is Mine (2001), another 15-minute film, was declared Best student film at the equally defunct Southern African Film Festival. He also did Special Delivery, another short before moving on to script for Studio 263, a popular television soap in Zimbabwe that also airs in Zambia and Tanzania.

RELATED: China Reaches Top Three in World Rankings

Tanyaradzwa tackles adolescence reproductive health while Masiiwa documents the life of celebrated Zimbabwean sculptor Dominic Benhura. The producer of Masiiwa, Daves Gutza, said it is important to make films on local artists while they are still alive instead of waiting for them to die in the fashion of politicians to be buried in the “Heroes Corner” in Harare.

Mupengo said there is “hunger for local productions in Zimbabwe” as not many films are made in that southern African nation.

Although many young people I spoke to were all set on leaving Zimbabwe, Mupengo said he just wants to make films in Zimbabwe.

“Though I am urged to go abroad, I am not interested to emigrate.”

Most films made in Zimbabwe, like everywhere else in sub-Saharan Africa, are mainly donor-driven.

“Tanyaradzwa was purely artistic, creative, and from an experience I thought could enrich people,” Mupengo says.

But isn’t it difficult making films in Zimbabwe due to lack of freedom?

“Not at all”, says Mupengo. “Artists have to know the environment in which they are working. There is nowhere in the world without rules. We shot in the streets without any harassment and so the situation in Zimbabwe is not as bad as some people try to portray it. There is censorship when it comes to political issues, though.”

At the time of our interview, Mupengo was working on another film project with film director Tsistsi Dangarembga.

A Rastaman who greets people in cinemas “in the name of His Majesty Emperor Haile Selassie,” Mupengo calls for co-productions among African Countries in the form of skills, stories, and finances, to “avoid tough conditions from foreign grant givers.”

“I have directed many of my scripts. I write and direct to protect and maintain my vision,” he says.

Benhura says he hadn’t sculpted before when he got to Harare in 1980.

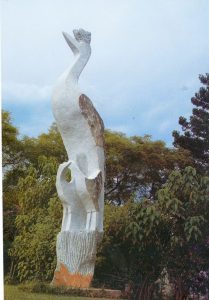

To venture in art, he abandoned Advanced Level mathematics, physics and chemistry. Today Benhura, who counts Tapfuma Gutsa as one of his mentors, is a respected artist who has traveled to almost every part of the world conducting workshops, exhibitions and residences. His stone sculptures are not only all over the world but Benhura has received numerous international awards for his work. He also paints and designs his own denims.

He says Masiiwa: A love for life documentary on his work, is meant to encourage parents to allow their children to pursue art as a career.

Benhura lamented that depressed economy in Zimbabwe adversely affected the arts scene as art depends on tourism. He runs a workshop that trains artists and supplies sculptures to the market. He is married with five children.

Unlike countries like Kenya that lack cultural institutions, Zimbabwe has the National Arts Council of Zimbabwe (NACZ) to serve the arts community. This is a para-state organisation that promotes and fosters the development of the arts and culture.

RELATED: Kenya Airways in Ambitious Expansion Plan

It awards National Arts Merit Awards (NAMA) to artists annually and has an Arts Development Fund to assist artists and arts practitioners. NACZ has a loan scheme for those who wish to borrow money. In the wake of socio-economic problems facing Zimbabwe, perhaps it is only NACZ that makes it possible for artists to continue interacting with the international community. They provide recommendations for artists going abroad and in the procurement of visas, and passport and grant-application. NACZ enables filmmakers to buy duty-free production equipment as long as they are not for resale. However few are using NACZ for lack of money in Zimbabwe.

Norbert Fero, a videomaker-cum-commissioning editor for Zimbabwe Television (ZTV), is working on a new film project, Up My Sleeve, that he says must be shot on 35 mm film in South Africa.

“I would like to leave the country now and produce it in South Africa,” he says.

Although Fero had just been rehired as Commissioning editor for ZTV after being fired when we met, he said he was ready to turn around the station that he described as being in a shambles.

“I want to be instrumental in changing this perception. I have been given freedom to make effective input in our programming. I want to encourage independent producers to negotiate with us as partners.”

Although Professor Jonathan Moyo had been seen as intolerant during his heydays as a powerful information minister before he fell out with President Mugabe, Zimbabweans credit him with having created an enabling environment for the arts and artists.

Moyo not only caused parliament to legislate that 75% of broadcasts on radio and television carry “local content” but that newspapers carry news on arts and culture on daily basis.

Such stories even appear on the front pages and not just inside pages as is the case in East Africa.

Many artists say this policy was good but regret it is “un-implementable in our current circumstances.”

Steven Chigorimbo has been involved in more than 60 film projects made in Zimbabwe as First Assistant Director and was for a long time involved with FEPACI matters in southern Africa.

He says every African Country should have at least one film festival to market films, promote and connect people.

Chris Timbe, director of Zimbabwe College of Music, laments that people can’t drive to school for lack of petrol while fees is not paid in time, while the money paid by students is hardly enough to run the college.

“Grants could assist but donors no longer give aid to Zimbabwe. I feel the government should encourage companies to give to artistic and cultural institutions and make this tax-deductible for us to survive.”

Raphael Chikukwa returned to Zimbabwe from South Africa in 1998 to work as an independent art curator.

The outspoken Chikukwa says ” ‘Politics’ is hindering his work. They want to separate art from politics, but you can’t”.

The exhibition he curated at the Harare International Festival of the Arts, HIFA, was “censored” with the organisers who wanted to curry favours with the authorities by rejecting certain photographs.

“I had wanted to bring photography in mainstream art. As I couldn’t do it within Zimbabwe, I was forced to do it in Manchester, England, to educate people that cutting edge art is coming out of Africa. And that this is not just curiosity or exotic art from a dark continent.”

Having been based at the National Gallery in Harare before the Manchester event, Chikukwa says he is suddenly not welcome at the gallery any more.

“The National Arts Gallery treats me like an enemy,” he says of the institution in which he had created a forum, “Breaking the Boundaries”, for artists and arts lovers to deliberate on art. But , he says, he suddenly discovered he could not bring artists into the country.

“I am planning to leave Zimbabwe,” he says.

Chikukwa says he had come up with Breaking Boundaries Arts Critics Forum to inject professionalism in journalists as they are not well versed in the arts.

“Give artists a voice. Don’t silence them” is Chikukwa’s appeal to Zimbabwean authorities. “We can’t be vibrant if we are censored”

RELATED: Why Tanzania’s Appeal as a Tourism Attraction is Waning

Chirikure Chirikure is a poet, novelist and musician.

He says ‘Operation Restore Order’ that the Zimbabwean government carried out in major towns in the country has denied people livelihood.

“Flea markets were closed, kiosks cleared away and this has disrupted average creative minds in Zimbabwe. ‘Operation Restore Order’ shook us up.”

Among the institutions he feels are supporting arts and culture in Zimbabwe are Amakhosi Community Initiative (Bulawayo), Rooftop Promotions (Harare), Harare Festival of the Arts, and Book Café (Harare).

And like one would expect in any part of the world facing problems, various kinds of churches are mushrooming up all over Zimbabwe, making many people to worship under trees and makeshift buildings.

Book-publishing is complicated and expensive in a nation with no money. Transforming creativity into books and selling them is a challenge.

Chirikure, listed as one of the five best Shona writers, says Zimbabweans will overcome current problems.

“As a community of artists in Zimbabwe, we have never been closer than we are now. There is lots of collaboration among us”, he says. “I have published three poetry books while a fourth one is on the way.”

He is currently working on an anthology in Shona (Zimbabwe), Xhosa (South Africa), French (France) and English (UK). It will be published in Zimbabwe. He has also recorded an album to Mbira music.

His books include Rukuvhute (1989), Chamupupuri (1994), Hakurarwi-iwe (1998), and Zviri Muchinokoro (2005). He has also published Mavende Akiti (children’s stories), Grade Seven Shona Revision, Junior Certificate Shona and Study Guide to Charles Mungoshi’s “Makunun” Unu Chirikure writes about colonial Africa, the struggle for independence, post- independence struggles, family, social issues, and African brotherhood.

But how does he manage to keep out of trouble?

“Only when your work is performed do you become visible to authorities,” he explains. He says he has had several brushes with overzealous agents of the state who tried to harass him.

He also says that he has been denied media coverage and sidelined. Prof Moyo had ordered a ban of his performances and airplay, he says.

Although many of his poems were composed and published before the onset of opposition politics in Zimbabwe, he says some of them, like Nappy, are interpreted to mean castigating the ruling ZANU-PF. This is just like when Thomas Mapfumo was accepted during the struggle for independence but targeted after independence.

The 1962-born Chirikure is involved in film, scripting, music lyrics, interprets music for inlays of Oliver Mtukudzi, has written a song for Mtukudzi and works with mbira queen Chiwoniso Maraire.

RELATED: Tourists Flood ‘The Island of the Gods’ as Top 5 Offbeat Travel Tours Are Unveiled

He coordinated poetry during HIFA and often consults for Zimbabwe International Book Fair, ZIBF. He says things are bad for artists in Zimbabwe.

“Arts are usually the first victims in depressed economies. We live by the grace of God as people have to choose between buying a book and food. We survive by performing for the more than three million Zimbabweans in the Diaspora.”

Joyce Jenje-Makwenda is a filmmaker and journalist. She has researched and documented Zimbabwe Township Music.

In her book and film, Jenje-Makwenda says people from all over Zimbabwe, Malawi, South Africa, Zambia, Mozambique, Tanzania all mixed in this melting pot of cultures that spawned township culture that gave birth to township music.

“I was just a housewife when I embarked on this project,” she says.

It was after she started being invited to give lectures in colleges and universities that she realized what she was doing was valuable to humanity.

“I got my first funding to do this project when I visited Sweden,” says Jenje-Makwenda. “I now have an archive of music , 300 songs dating from 1929 to the 1970s. The first song recorded in Zimbabwe was in 1929.”

Jenje-Makwenda says she had just wanted to do the book but that she was persuaded by people to make a documentary film on it as well.

“I just completed form four and didn’t do much till after my four children had grown up. I funded my research from making and selling samosas. I slept for less than three hours a night as I was bringing up my children and studying journalism via correspondence. I did my first documentary in 1992 and it won an award. Since then I have been giving lectures on Zimbabwe township music. I got money from NORAD in 1994 and from Ford Foundation in 2003 to complete publishing.”

She has done about 10 documentaries since then: five on music, others on women.

“Early urban settlers fused traditional music with Jazz that became the main fusion. It had come from here to America and back via electronic media. Jazz is our tradition. It isn’t western but African. Early township music was not just Jazz but also Kwela, Amarabi and others. Township music changes according to time and environment. I am now writing another book on music from the 1970s to now,” she says.

Among the awards the self-taught Jenje-Makwenda has won include Best TV Producer of the Year at Reuters’ National Media Awards (1993), Freelance Woman Journalist of the Year at UNIFEM, Federation of African Media Women of Zimbabwe (FAMWZ) 1999, and Population and Gender Writer of the Year (UNFPA,Zimbabwe Union of Journalists) in 2002.

By September 2005, Alick Macheso had sold more than 1.3 million copies of his sungura music albums over the past eight years, making him the best selling musician in Zimbabwe.

His first album, Magariro, sold over 140,000 units, with follow-up albums Vakiridzo selling 130000, Simbaradzo 300,000, Zvakanaka Zvakadaro 250,000 and Zvido Zvenye Kunyanya 250,000.

The latest, Vapupuri Pupurai, had by end of August 2005 sold 160,000. Macheso is therefore the highest selling musician in the history of Zimbabwe’s music and has surpassed sales by such big names as Leonard Dembo, Oliver Mtukudzi, Thomas Mapfumo and Simon Chimbetu. Although Mtukudzi sells more CDs and mainly abroad, Macheso is stronger on tapes and mainly at home.

Among the leading urban groove musicians are Afrika Revenge, an Afro-jazz outfit whose latest album is Qaya Music. This duo of Mehluli Moyo and Willis Watafi rose to fame after their song, Wanga, became a hit on national radio and won them Best Afro-Jazz outfit and the Best Male Artiste Award at the Zimbabwe Music Awards in 2004. The song also won them the Outstanding Album Award at the National Arts Merit Awards in February 2005. The group did the soundtracks for the film, Tanyaradzwa: The Sun, Things Have Gone wrong.