To write as Kenyans speak, live and breathe is what Kwani?, Kenya’s literary periodical (magazine/journal/book?), sets out to do. With its third edition out, it is apparent that to do this and remain within the parameters of good literature requires enormous skill that may not be easy to attain. For that reason, most literary giants, starters, students and under-the-tree-shade readers have dismissed Kwani? as ‘lacking in intellectual content and context’ or as being a ‘playful’ work. Mwenda wa Micheni writes.

To write as Kenyans speak, live and breathe is what Kwani?, Kenya’s literary periodical (magazine/journal/book?), sets out to do. With its third edition out, it is apparent that to do this and remain within the parameters of good literature requires enormous skill that may not be easy to attain. For that reason, most literary giants, starters, students and under-the-tree-shade readers have dismissed Kwani? as ‘lacking in intellectual content and context’ or as being a ‘playful’ work. Mwenda wa Micheni writes.

Binyavanga Wainaina, editor of Kwani?, appears in his SHOUTING editorial to be guilty as charged as he rants and raves. He is at pains lamenting at the reception of his work. He does not only refer to the works before his as ‘the same old people talking to each other,’ but proceeds to claim the popularity of Kwani? and, like a non-performing National Rainbow Coalition (NARC) politician, blames the ‘Moi era’ for people who point out his shortfalls. In that one hears a Kenyan speak, live and breathe! A Kenyan who does things deliberately the wrong way hoping that nobody notices, and who takes critics as enemies. A self-righteous superstar with a ‘bitter sense of territorialism.’

This spreads out throughout Kwani? 03 in what Kenyan Afro-fusion musician Lydia Achieng Abura would refer to as ‘celebrity nonsense’.

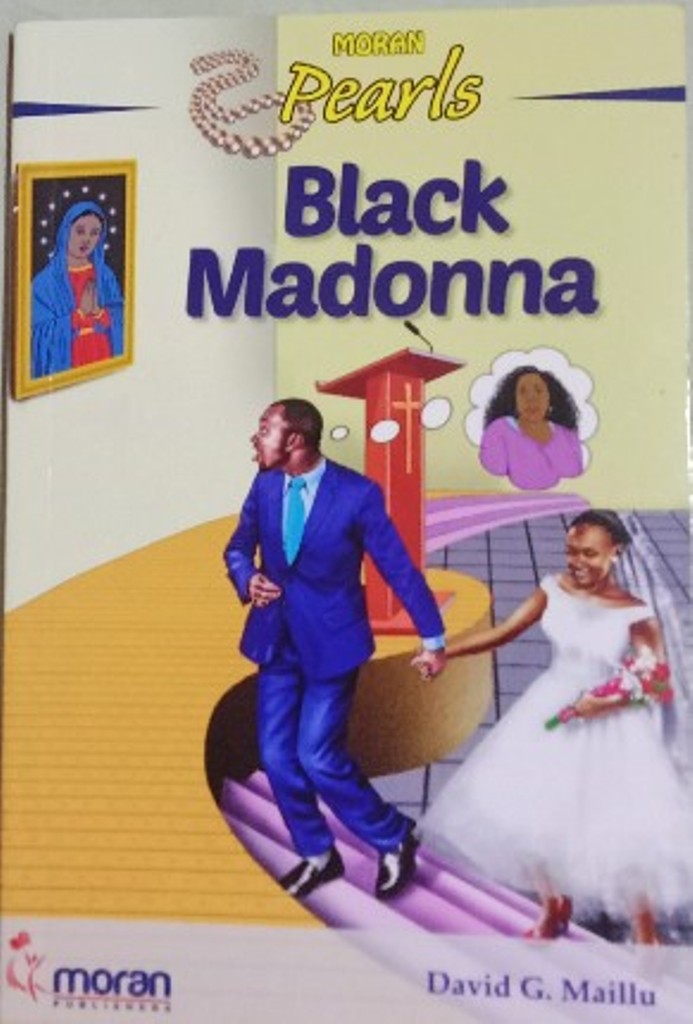

Granted, the cover has been attractively re-designed as a film promotional poster or cover of a popular literature novel: the artwork, colour scheme and fonts have a great visual appeal.

RELATED: Kwani?2 Boosts Kenyan Literature

The removal of a dread-locked image from the cover that has graced the previous two editions and given the publication the image of defiance and anti-establishment stance is a welcome relief. But then Kwani? owners have simply transferred the picture to page 5 on which they stress to the reader: ‘notice the short dreads’. The picture here is described as ‘a rare photo of Dedan Kimathi’. As to their obsession with dreadlocks, Kwani? publishers do not tell the reader.

The kind of paper used in the inside pages of Kwani? does not appear to be good enough for the proper registration of black and white pictures. Moreover, the black background of Chief Wambogoo’s pictures and calligraphed tiny writing makes captions difficult to read. In some instances, the type size appears to be too small (10?) and makes the print difficult to read.

Unlike most publications, the covers of Kwani? are counted though the page numbers do not appear on them. It is only from page 6 that one deduces that covers are also numbered.

At the risk of being regarded a philistine, I still do not get what most poems (or are they prose masquerading as poetry?) are about.

Then again, one would like to know what the ‘Photos of Hairstyles 1950-1960 French-speaking Africa’ are about if not just to fill up space’.

The people whose stories appear in Kwani? are introduced as ‘Starring’ while writers are ‘Featuring’ on the cover.

Binyavanga Wainaina is called ‘the King of Lateral Thinkers’, while Muthony (or is it the Gikuyu ‘Muthoni’?) wa Gatumo is a ‘veteran Kwani? writer.’ Yet this is just the THIRD publication. Has the English term ‘veteran’ as we know it gained another meaning?

Like other mysteries in the book, one may not know why cartoons from JOE magazine of the 1970s, a picture of ‘Newly-wed Mr & Mrs Hosea Kaugi’, ‘Miss Elizabeth Murunga & Miss Wambui Kezia in 1972’ and ‘Miss Jacinta Murungo’ (who are they?) and adverts are included in Kwani?

Muthony wa Gatumo’s ‘Transitions’ exposes life, talk and expectations of the city dwellers’ especially of those belonging to self-imposed group, creed and class. (Pg 404)

In Mwas’ Captured (Pg 378) you are left totally uncaptured even after struggling to read the piece more than twice. It is like being forced by a school teacher to imitate a retarded child’s way of talk or being taught English and Kiswahili together in the teacher’s mother tongue. It reminds you of how some words flow when spoken yet are bulky to the eye and brain, and are irritating when written for you to read.

Serious themes of insecurity, retrenchment, drug peddling, corruption and teenage sex that Mwas strives to address disappear under his language. It is also revealed that Mwas, ‘the sheng guru for Kwani?’, has his facts reversed. According to him, ‘local Kenyan music has just become confident enough to use local language’, and therefore he is looking forward to the time when Kenyans will ‘create Kenyan sound using local rhythms, instruments and beats.’

RELATED: Kwani? Flouts Writing Rules

Would he be referring to the current crop of playback singers of, say, ‘Genge’ and ‘Kapuka’? It makes one wonder where he places the traditional instruments, rhythms, beats, indigenous languages and the musicians that have all along been in Kenya, like Gabriel Omolo, and the late Fadhili William and Daudi Kabaka and whose popularity has gone beyond the East African nation’s political boundaries.

‘Blood and 100% human hair’ by Martin Mbugua Kimani, addresses issues like tribalism, poverty, entrepreneurship, and eroded family values and structure. “I am irritated that he assumes we share a common animosity against the woman. But he means well ‘ it is an invitation to be part of a Gikuyu nationhood whose twin pillars are a universal sense of entitlement to the fruits of Kenyan nationalism, and a fear of Luo competition. So even here, shoulder-to-shoulder, as spectators and not combatants, we belong to disparate communities and are conscious of the battle for supremacy.’ As your mind whirls about how Kenyans speak, live and breathe, you shouldn’t miss Muthoni Garland’s often good nurtured dung-smearing kind of talk (mchongoano) common among Kenyans and that sometimes leads to anger and animosity and, most times, tears of laughter. This is Eating. She says, “In Dundori, it is said, people knocked on the doors of buses to seek entry; planted bones hoping to harvest meat, farmed akiba potatoes as big as a Dundori man’s head (and with hollow centre to match), and carried sacks of the said akiba on their laps so the bus wouldn’t tire.” As already mentioned in this article, it is only in Kwani? 03 that one also finds prose written in columns; words jumbled up in order to appear poetic or lyrical, very good poems, three decades old conversation art (cartoons and illustrations), ‘intellectually sound’ stories, archival pictures and some stories that wouldn’t make a Kenyan daily talk. For instance, there are the stories of Chief Wambogoo, Bessie Smith ” The Empress of Blues, and Jackob Njiiri Daniel. Who are they and what would interest a Kenyan in them? If there is a Kenyan who speaks, lives and breathes these kind of stories, then perhaps he is the kind who wouldn’t read Kwani? Which brings us to the question of whether Kwani? has a specific target audience and if it is focusing on that audience? Or it may just be a question of testing the waters hoping that the stick hits the base! Buzz and Pulse, the juvenile entertainment pullouts of Sunday Nation and The Standard newspapers, respectively, that only revel in celebrity gossip and rumour mongering, have their audience, too ” the playful and up-and-coming anything who dream of stardom. Expectedly, this group, though relatively small, has its language. Sheng! But whose Sheng? Sheng, though spoken by many people, old and young, has never and probably will never be standardised. Neither will it attain universal level of acceptance. In Nairobi alone, the slang varies depending on the region — Eastlands, Westlands or Southlands — or social, education and ethnic background of its users. In Eastlands virtually every estate has its unique version of sheng. Sheng spoken in Kisumu is riddled with reversed Dholuo terms, while in Mombasa and the icing is likely to be Kiswahili, Arabic or Mijikenda dialects. Sheng is also an enemy and fugitive of itself that seems to be in constant escape from itself.

Once a word gets common, it becomes outdated and is quickly replaced. A slang meaning one thing to a certain people can mean another thing elsewhere. That is why documenting sheng as a way of coming up with a structure where ideas are communicated as in Kwani? may be deceptive, pretentious, presumptuous and discriminatory. It borders on the selfish belief that if I understand then they have to understand unless they are daft! That not having is their own foolishness, and therefore I am entitled to more! Who determines the spellings of sheng words and who ascertains their standard and level of acceptability? It is as a result of such questions that drives one to believe that Kwani? would simply be targeting a small clique of Nairobians who can frequent Carnivore, K2 or Kengeles for over-the-drinks reading sessions, while it strategically hides under the mask of representing Kenyans. More than 30 million people from 42 ethnic and diverse social backgrounds can only speak, live and breathe one language if that language follows specific set standards and regulations. This may explain why Dayo Forster, a Zambian living in Kenya, maintains proper language in his ‘The Deed’. We are told in Kwani? 03 that.

There is another Kenya growing out of these ashes. It has learnt to need nobody; to be competitive and creative. It speaks Sheng. It is the Kenya we are waiting for. “This sounds much more like a revolutionary call against serious literature and makes one wonder whoever is being referred to as ‘we’. In case this message is targeting the vulnerable youth “those whose reasoning, talking, dressing, walking or singing is influenced by 50 Cent, Sean Paul or Akon ‘ then it is a dangerous activist’s call to come from a person who presumably stands for liberal minds. Players in the literary world are needed to be creative and competitive like nowhere else. It is only through the attainment of high standards that we will not be tempted to revert to escapist routes that would lead us to our own territories where we only abide by our own rules and standards. But this is not to say that Kwani? does not have its place in society. It is ‘place for seekers.’ And the fact that it doesn’t “prescribe” enhances creativity, openness and ‘career possibilities’ for some. And some people “love it very much.”