By Ogova Ondego

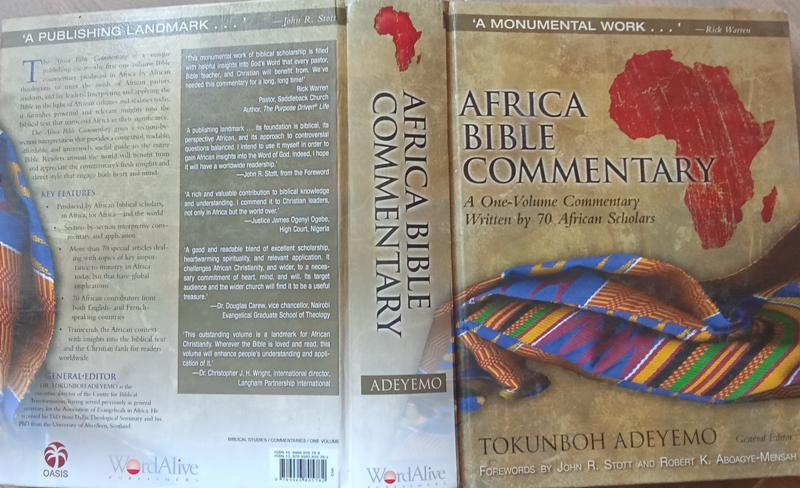

Described variously as a ‘publishing landmark’ and ‘monumental work’, this post-modern Africa Bible Commentary (ABC) is touted as having a sound biblical foundation, an African perspective and a balanced approach to controversial issues. OGOVA ONDEGO writes.

Described variously as a ‘publishing landmark’ and ‘monumental work’, this post-modern Africa Bible Commentary (ABC) is touted as having a sound biblical foundation, an African perspective and a balanced approach to controversial issues. OGOVA ONDEGO writes.

The single-volume ABC is written by 69 scholars drawn from 23 countries and the editorial board says it will soon be translated into French, Kiswahili, Amharic, Yoruba, isiZulu, Afrikaans and Portuguese.

Unveiled at the Cape Town Book Fair on June 19, 2006 and launched in Nairobi by retired Kenyan president Daniel Toroitich arap Moi on July 5, 2006 in an event that was widely covered by the local and international mass media, ABC appeared to suffer a blow when the Roman Catholic Church in Kenya cautioned its followers on August 2, 2006 that its message be looked at critically ‘by people who understand its stance’ and that ‘It should certainly not be used with an understanding that it is faithful to Catholic teaching’.

“Used uncritically,” the church said in a statement signed by Archbishop John Njue, the Commission for Doctrine of Kenya Episcopal Conference, ABC “is certainly problematic.”

The Catholic Church said it does not accept the position of ABC on issues like homosexuality, the role of women in the church, marriage and divorce, and the relationship between the church and the state as it “conflicts with Roman Catholic teaching.”

The Roman Catholic Church also rejected ABC for what it termed “fundamentalist approaches to interpretation”.

“The fundamentalist approach is dangerous, for it is attractive to people who look to the Bible for ready answers to the problems of life. It can deceive these people, offering them interpretations that are pious but illusory, instead of telling them that the Bible does not necessarily contain an answer to each and every problem,” the statement read. “…fundamentalism invites people to a kind of intellectual suicide. It injects into life a false certitude, for it unwittingly confuses the divine substance of the biblical message with what are in fact its human limitations. ”

In a rejoinder on August 17, 2006, the ABC Editorial Board said their commentary is not bound to Catholic teachings as it is intended for Protestant evangelicals in Africa. The board regretted what it termed “the overall negative tone of the statement by the Catholic Church of Kenya as “The Africa Bible Commentary has received international acclaim as a great work of African Christian scholarship. It has been said to stand in the same tradition as the great African Church Fathers such as Augustine and Athanasius.”

In a rejoinder on August 17, 2006, the ABC Editorial Board said their commentary is not bound to Catholic teachings as it is intended for Protestant evangelicals in Africa. The board regretted what it termed “the overall negative tone of the statement by the Catholic Church of Kenya as “The Africa Bible Commentary has received international acclaim as a great work of African Christian scholarship. It has been said to stand in the same tradition as the great African Church Fathers such as Augustine and Athanasius.”

The statement concluded: “The Africa Bible Commentary is an invaluable resource for every Christian who wants to understand the Word of God in the context of contemporary African realities. It is indeed a treasure for the church in Africa and the world.”

But why come up with a tome such as ABC?

“Despite the vast number of African Christians, the new churches springing up every day, the all-night prayer meetings, exorcisms and the days of fasting,” writes Ugandan Lois Semenye, “the continent is still blighted with poor government, bribery, killings, coups, the AIDS epidemic and so on.” And this, she contends, has been the case since the 1960s when Christianity in Africa was described as being a mile long but only an inch deep. Lack of proper education is partly to blame for this, Dr Semenye argues.

“Despite the vast number of African Christians, the new churches springing up every day, the all-night prayer meetings, exorcisms and the days of fasting,” writes Ugandan Lois Semenye, “the continent is still blighted with poor government, bribery, killings, coups, the AIDS epidemic and so on.” And this, she contends, has been the case since the 1960s when Christianity in Africa was described as being a mile long but only an inch deep. Lack of proper education is partly to blame for this, Dr Semenye argues.

Written from what is described as the Evangelical Christian perspective, ABC, writes the general editor of the book, Nigerian Tokunboh Adeyemo, was aimed at interpreting the Bible to Africans in familiar language, using metaphors, “African thought-forms and nuances, and practical applications that fitted the African context.”

The idea to produce ABC sprang from the Second Pan African Christian Leadership Assembly (PACLA II) in September 1994 when 1200 Christian leaders gathered in Nairobi identified “deficient knowledge of the Bible and faulty applications of its teachings” as being culprits for the fast-growing but largely ineffective church in Africa. This, explains Dr Adeyemo, gave the leaders the burden to interpret the Bible in a familiar language to enable Africans to easily internalise its message.

Quoting St Augustine of Hippo, Kenyan Aloo Osotsi Mojola says God is closer to a people when he is presented to them in their language.

What is most appealing about ABC are the special articles on topical and cultural issues in the mother continent.

What is most appealing about ABC are the special articles on topical and cultural issues in the mother continent.

Some of the topics in this tome that was printed in China include culture and traditions, homosexuality, bride-price, widow inheritance, the place of ancestors, the place of traditional sacrifice, polygamy, marriage and divorce, female genital mutilation, initiation rites, witchcraft, AIDS, secularism and materialism, the role of women in the church, the relationship between church and state, and democracy.

Ghanaian Kwame Bediako defines culture as “our world view, that is, fundamental to our understanding of who we are, where we have come from and where we are going. It is everything in us and around us that defines us and shapes us.” He then goes on to say that acknowledging the centrality of scriptures to one’s identity “does not mean that we demonize our own traditional culture.”

Appearing to concur that Africans are by nature deeply religious and that their approach to life is religious, Bediako says this could assist them in being more receptive to the scriptures.

Nigerian Eunice Okorocha stresses that “an understanding of the role of culture is of great importance both in understanding what the Bible says and in communicating this message in terms that are meaningful in relation to local culture and issues in Africa.”

She says readers must distinguish between elements of the Bible that are specific to Jewish culture and which have a universal application.

On the thorny issue of the role of women in the church, Kenyan Nyambura J Njoroge employs the usual stock words and phrases–deeply entrenched patriarchal, hierarchical and sexist attitudes and practices, and the male-dominated leadership in many churches–from the arsenal of feminists that have earned them more enemies than allies in urging readers against focusing on “the gender roles, that society, church and African cultures have assigned to women.”

On the thorny issue of the role of women in the church, Kenyan Nyambura J Njoroge employs the usual stock words and phrases–deeply entrenched patriarchal, hierarchical and sexist attitudes and practices, and the male-dominated leadership in many churches–from the arsenal of feminists that have earned them more enemies than allies in urging readers against focusing on “the gender roles, that society, church and African cultures have assigned to women.”

But Njoroge does not say why the ratio of female to male contributors to ABC is 3:7 or why women are only assigned to comment on ‘feminine’ books like Ruth and Esther or ‘feminine’ subjects like hospitality, female genital mutilation, rape, and bride wealth but not ‘masculine’ Introduction to the Pentateuch, The role of ancestors, or Christians and Politics. Could this be due to “the gender roles that society, church and African cultures have assigned to women”?

Nigerian Yusufu Turaki argues that the religious world view of Africans is threatened by the western philosophy of secularism that is opposed to spirituality.

Writing on homosexuality as ‘abnormal, unnatural and a perversion’, Turaki contends that the only kind of sexual relationship approved of God is the male-female one as it ‘can produce children and thus create the type of family God envisages, with a father, a mother and children.’

Taboos, Rather than being dismissed as mere prohibitions or superstitions, writes Ghanaian Ernestina Afriyie, should be examined to see what they reveal about God.

RELATED: Publisher of African Bible runs for President

Although he stresses that nothing–other than death or infidelity–can put asunder what God has united in marriage, Kenyan Samuel Ngewa nevertheless writes that ‘special’ cases, such as torture, financial neglect, extended absence, or threat to life that prove resistant to counseling, the church may recommend separation, divorce and remarriage.

Hey, then the church can separate what God has joined? This view, like that on The Church and the State by Turaki that says the church cannot ‘prescribe the details of what authorities must do or of the actions citizens should take, provided their actions are not contrary to God’s word,’ is difficult to comprehend.

Particularly objectionable could be the part that says the right of the government’ to rule is not rooted in the consent of the governed but derives from God. ‘

Widow inheritance in Africa, writes American Mae Alice Reggy-Mamo, conflicts with the Christian belief that death ends the marriage union.

“Allowing a widow to be taken over by an in-law constitutes a denial of that Christian belief because such an action is based on the view that the marriage contract continues even after the death of the husband.”

She laments that though “widows comprise nearly one-third of some congregations in Africa, the churches have neglected to deal with issues that affect them”, maintaining silence on issues such as widow inheritance that conflict with Christianity and which are like a death sentence in this era of HIV and AIDS.

Writing on Widows and Orphans, she notes: “in the past African widows did not experience the isolation and loneliness they do today. When a man died, his family cared for the widow, including her sexual and procreative needs.”

With the coming of Christianity, Reggy-Mamo writes, “some aspects of African culture were abandoned. Now it is up to the churches to go back to their African roots and recover what was good, such as the earlier loving care for widows and protection of orphans by the community.”

But how long ago were these African values lost? How can African churches of the 21st Century go back to ‘African roots’ they never had? How did the family of a dead man in traditional Africa care ‘for the widow, including her sexual and procreative needs’ and how can a postmodern African church embrace this?

Malawian Isabel Apawo Phiri says polygamy dehumanizes women. It shows a lack of respect for the dignity of women as full human beings, created in the image of God.

According to Phiri, gifts that a man’s family gives to the family of the woman he wishes to marry–lobola, mahari, bride wealth, bride price–binds two families together and legitimises the marriage. Besides giving a marriage stability, bride wealth has spiritual aspects as it involves rituals that inform the ancestors of the families about the marriage relationship and seeks their protection.

What Phiri does not explain is that once such a union has been entered into in Africa not even death can end it as in the western culture that states that “till-death-do-us-part”. It is on this basis that ‘widow inheritance’ is conducted, the widow remaining the wife of the deceased–the grave–and not the ‘guardian’ or ‘protector’ who takes over.

As belief in ancestors is fundamental to traditional Africa thinking, suggests Turaki, ‘African veneration, worship and respect for the ancestors should now be properly addressed to Jesus as the mediator.’ Nigerian Samuel Waje Kunhiyop claims that ‘belief in witchcraft is approaching epidemic proportions in Africa’ and that even Christians are dabbling in it.

Instead of seeking to understand it, church leaders usually dismiss witchcraft as mere superstition. Kunhiyop appeals to the church to urgently address this problem ‘with seriousness, sensitivity and respect.’

It is contradictions and inconsistencies that tempt one to wonder if the writers worked as a team, critiquing one another’s work and seeking to harmonise it for a landmark work like the ABC. Nevertheless, ABC is interesting in the sense that it provokes discussion on thorny issues between western and African cultures.

Christianity may have been born in the Middle East, a region whose cultures are similar to those of Africa. However, it was introduced to Africa through the western worldview that is diametrically different from that in most African and Middle Eastern countries. It is on this premise that one would wish for logical, coherent and convincing views on why, for instance, veneration of ancestors, widow inheritance, or bride wealth, are wrong in western-styled Christianity.

Culture not only refers to a people’s practices, values, beliefs and aspirations but also shapes their existence. Created over generations from a people’s experiences and relationships, certain cultural practices could look irrational to the uninitiated but this is the context in which a people construct their identity.

I would have labeled ABC as engaging in doublespeak and ambiguity to confuse and thus avoid responsibility as some of its articles border on simplicity but then I note the disclaimer by its general editor: “The ABC is not a critical, academic, verse-by-verse commentary”.

But why is it not? Is ABC not meant to equip leaders at the grassroots–pastors, students, lay leaders–with sound knowledge to pass it on to the wider society in order to influence it?

ABC may be an asset to Africa, but its value would have been enhanced through a diversity of opinion, especially on topical issues. One wonders why a few writers, though great and opinionated they may be, dominated here as if they were delivering a sermon from the pulpit. Turaki, for instance, wrote eight articles on diverse subjects–Democracy, Homosexuality, Secularism and Materialism, The Bible, The Church and the State, The Role of the Ancestors, Violence, and Truth, Justice, Reconciliation and Peace–while Ngewa and Adeyemo each did seven articles. Thus 32% of the 69 articles were contributed by three people as if they were writing for a daily newspaper.

Funded by Serving In Mission (SIM) and Association of Evangelicals in Africa (AEA), editorial contributors to ABC came from Angola, Benin, Burkina Faso, Central Africa Republic, Chad, Congo-Kinshasa, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Ghana, Ivory Coast, Kenya, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Namibia, Nigeria, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, Uganda, United States of America, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

ABC is published and distributed by WordAlive Publishers and The Zondervan Corporation in Africa and the rest of the world, respectively. It is also distributed by Oasis in Africa.