By Ogova Ondego

Published December 29, 2014

I was intrigued when I received an email from a Kenyan American a couple of months back saying, “I have authored a book about the Maragoli of Kenya in response to my daughter who once asked me if Nelson Mandela was the president of Africa.”

I was intrigued when I received an email from a Kenyan American a couple of months back saying, “I have authored a book about the Maragoli of Kenya in response to my daughter who once asked me if Nelson Mandela was the president of Africa.”

RELATED: Play that Confronts Historical Injustice in Kenya Opens in Nairobi

The writer, James M’Mbuka Ndeda Ojago, a medical doctor based in United States of America, wondered whether I could review the 322-page book titled Letters from My Dad: The Roots of a Maragoli Family of Kenya.

Well, I have just read the book that costs US$14.95 per paperback and US3.63 per e-book and whose content appear not to be addressed to Dr Ojago’s inquisitive daughter but to his American friends, Mr Brown and Mr Maliki Jabir who are described as Africans in the Diaspora.

RELATED: How Nelson Mandela and Thabo Mbeki’s ANC Betrayed South Africans

The writer says his intention in writing the book that is classified as being autobiographical, biographical and anthropological is “to make the World aware of our rich Black African heritage, be it from western Kenya or from anywhere in the Republic of Kenya, for if we do not do it, who will?”

And the son of Andimi (as the Maragoli are sometimes referred to) begins with his own community on the premise that “charity begins at home”.

The writer not only defines the term ‘Maragoli’ and traces the community from its foreparents, Andimi and Mwanzu in present southern Sudan/north-eastern Uganda and their son and daughter-in-law Mulogoli and Kaliyesa who migrated with their four sons to an area around Maragoli Hills in present western Kenya but also describes the ‘Maragoli territory’ in Kenya’s Vihiga, Nyaribari, Kanyamkago, Migori and northern Rift Valley areas like Lugari, Mautuma, Kamukuywa, Kitale and Eldoret, the Mara/Serengeti animal migration area of Tanganyika (Tanzania mainland)Â and Kigumba area near Uganda’s Masindi Port.

However, as he tells the story of the Maragoli who come across as a highly enterprising individualistic community with a strong work ethic, Dr Ojago is also telling the story of the East African modern nation-state known as Kenya.

The author describes the arrival of white American missionaries at Kaimosi in Tiriki, just north of Vihiga in 1902, as “the most significant event that had broad ramifications for members of the community.”

RELATED: State Repression Turns Eritrea Into A Large Prison

Dr Ojago writes the Quakers (as the missionaries who set up their Friends African Mission in Kaimosi are known) “could never have found a better location in the [Kenya] colony, as the community seemed to awaken and embrace these white foreigners and their way of life with repercussions in terms of literacy, improved healthcare, reduced infant and maternal mortality, increased crop production and even outward migration.”

Dr Ojago writes the Quakers (as the missionaries who set up their Friends African Mission in Kaimosi are known) “could never have found a better location in the [Kenya] colony, as the community seemed to awaken and embrace these white foreigners and their way of life with repercussions in terms of literacy, improved healthcare, reduced infant and maternal mortality, increased crop production and even outward migration.”

The Maragoli, Dr Ojago writes, “embraced the Quakers, their education and ideas like no other neighboring community did. Early pioneers of education from the mission acted as agents, returning to their own neighborhoods as teachers and church pastors.

An ethnic male had swapped a hunting spear and a dog for a pen and a book; a cow or monkey skin wear for western wear; a monkey skin hat for a western hat; local alcoholic beverages for chai tea. Things were never the same in the community.”

RELATED: Ethiopia Should Stop Spying on Opposition at Home and Abroad

Migration out of Vihiga County that is home to the Maragoli, Tiriki and Banyore and that Dr Ojago says “supports one of the highest population densities in Kenya and indeed the whole world,” was encouraged by the British colonial powers as a way of easing pressure on the densely-populated land from 1936.

Though the encounter with the missionaries is presented as having been mainly positive, that wasn’t the case with the European settlers and the Indians who had been brought to the then British territory by the colonial government as labourers on the Kenya-Uganda railway line.

RELATED: Continental Court Could Perpetuate Impunity in Africa

Dr Ojago writes that the colonial administration set up an apartheid state in Kenya: “At the highest level of society was the white race; second in the caste were people of Indian descent, from the Indian subcontinent… At the lower end of the caste were members of the African race. Every aspect of daily life was segregated.”

Dr Ojago writes that the colonial administration set up an apartheid state in Kenya: “At the highest level of society was the white race; second in the caste were people of Indian descent, from the Indian subcontinent… At the lower end of the caste were members of the African race. Every aspect of daily life was segregated.”

RELATED: The Sh51,000,000,000,000,000 ‘Donor Aid’ Question Comes to Nairobi

By 1904 the Indians in Mombasa were “demanding land and other property in the highlands in the same manner as the European settlers. In 1909, Alibhai Mulla Jevanjee, a local Indian businessman and politician was appointed by the colonial authorities to the ruling Legislative council … Indian politicians of the day initiated a campaign to annex Kenya as an Indian colony that could be administered under an Indian Viceroy. Jevanjee travelled to London in 1910 to advocate for the Indian case.

His action having displeased the white settlers, Jeevanjee was removed from the Legislative Council. But that didn’t deny Indians the rights and privileges they enjoyed but that were denied to the African majority, James Ojago contends. “Indians represented a daily reminder to my community of colonial economic exploitation. By the 1950s Indian merchants were everywhere, including the most remote ethnic neighborhoods of the colony. They had found a niche in the colony way beyond what any of them could have experienced on the Indian sub-continent.”

RELATED: BBC Africa Debate to Discuss Failed Health Systems in Africa

In a not-so-flattering language, Ojago writes: “The Indians treated their African clients and employees as dogs or as members of a subhuman race whenever an African client did business with them. They have a caste system over in India which they imported to the colony, to a place where they were guests. An African client could expect to face abuse, even after spending cash purchasing products from the Indian businessman. For example asking a follow up question related to price or window-shopping were actions that could attract the wrath of the Indian.

In a not-so-flattering language, Ojago writes: “The Indians treated their African clients and employees as dogs or as members of a subhuman race whenever an African client did business with them. They have a caste system over in India which they imported to the colony, to a place where they were guests. An African client could expect to face abuse, even after spending cash purchasing products from the Indian businessman. For example asking a follow up question related to price or window-shopping were actions that could attract the wrath of the Indian.

Their business ethics were questionable and Africans couldn’t even count their change subsequent to a purchase, as it was misconstrued as provocative behavior. The Indian would go off in anger and employ the most abusive language he could come up with directed at his former client with full knowledge that the law was in his favor. Those Indian visitors disrespected our womenfolk, taking liberty with them and corrupting their morals.”

RELATED: Lifting the Lid on Rwandan Repression

And did the matter end with the corruption of the morals of the disrespected womenfolk by the Indians?

“After Kenya became a Republic in 1964, many of their kind would have nothing to do with Kenyan citizenship, opting instead to follow the British either to England or to Canada.

The few who retained Kenyan citizenship have continued to engage in shady business deals, including but not limited to price gouging, tax evasion, money laundering, gold and coffee smuggling, theft of petroleum products, smuggling of small arms and ammunition to rebel groups in the region, wildlife poaching and what have you, always in cahoots with corrupt elements in the government. When confronted with evidence, they are quick to flee the country for the safety of either India or Europe in order to evade prosecution,” he writes. “There is no current adult black Kenyan who can honorably vouch for a positive experience with an Indian merchant, either as an employee or as a client, in Nairobi City or any community where Indian merchants are currently resident.”

The book also describes Maragoli beliefs, traditions, rites of passage, marriage, pregnancy and childbirth, childhood, folklore (riddles, proverbs, and metaphors), education and entertainment (Bull-fighting, Isukuti dance), something that makes it possible for the reader to understand the community’s worldview and its relationship with its Luo and Nandi neighbours.

RELATED: Most African Countries Unlikely to Meet the 2015 Digital Transition Deadline

Though not tackled, the reader can make an educated guess on why the Maragoli and the Luo, though inter-marrying and interacting as any neighbouring communities would, appear to harbour prejudices against one another. One may also tell why the Babukusu of Bungoma, though lumped together with the Maragoli as Luyia, are uneasy with each other. Could this be due to what Dr Ojago refers to as the feeling of ‘entitlement’ that is exhibited by many aBalogoli whose language was ‘imposed’ on the other ‘Luyia’ through the hymns and Bible that were translated into Lulogoli?

Though not tackled, the reader can make an educated guess on why the Maragoli and the Luo, though inter-marrying and interacting as any neighbouring communities would, appear to harbour prejudices against one another. One may also tell why the Babukusu of Bungoma, though lumped together with the Maragoli as Luyia, are uneasy with each other. Could this be due to what Dr Ojago refers to as the feeling of ‘entitlement’ that is exhibited by many aBalogoli whose language was ‘imposed’ on the other ‘Luyia’ through the hymns and Bible that were translated into Lulogoli?

RELATED: Kenyan Protesters’ Use of Pigs, Vultures and Death Put Police in a Dilemma

The reader may be tempted to question why the writer does not delve deeper into the relationship between the Maragoli and their Luyia brothers and sisters: How did the Maragoli come to be grouped together with the Tachoni and Babukusu with whom they share so little as compared to the abaGusii (Kisii) whose language is similar to Lulogoli? Is it true that the Maragoli migrated from southern Sudan/north-eastern Uganda, a Nilotic dispersal area, instead of from the conventional central/southern Africa?

How much research went into this book? How much of it is factual?

“I was lucky enough during my childhood to have spent time in Kanyamkago in the late 1950s where my father was posted as a Teacher for the Friends Mission Schools. Thereafter he was transferred to Nyakoe in Nyaribari (Kisii), and later my family was among the first migrants to the Kenya Highlands at Kamukuywa in the middle of the 1960s. So what I describe in the book is from a personal experience,†Dr Ojago says.

He adds that he had family members among the migrants to Tanganyika and Uganda who “would come back from time to time and describe to me their experiences in those locales. The rest of the information is what I could remember growing up with my grandparents in the early 1960s at Kegoye primary school. And of course the rest of the information was gathered from my surviving uncles who are both in their 80s back home in Kenya.”

He adds that he had family members among the migrants to Tanganyika and Uganda who “would come back from time to time and describe to me their experiences in those locales. The rest of the information is what I could remember growing up with my grandparents in the early 1960s at Kegoye primary school. And of course the rest of the information was gathered from my surviving uncles who are both in their 80s back home in Kenya.”

RELATED: UN Declares Kenya and Tanzania as ‘˜The World’s Worst Elephant Slaughter Houses’

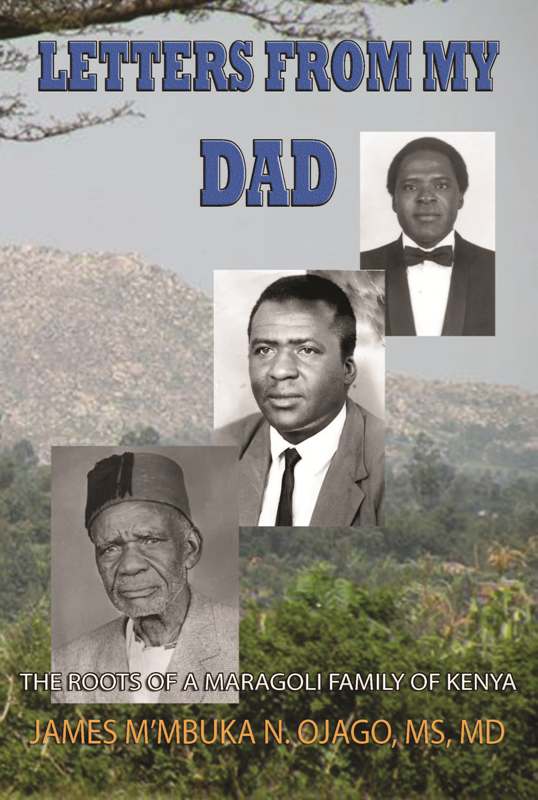

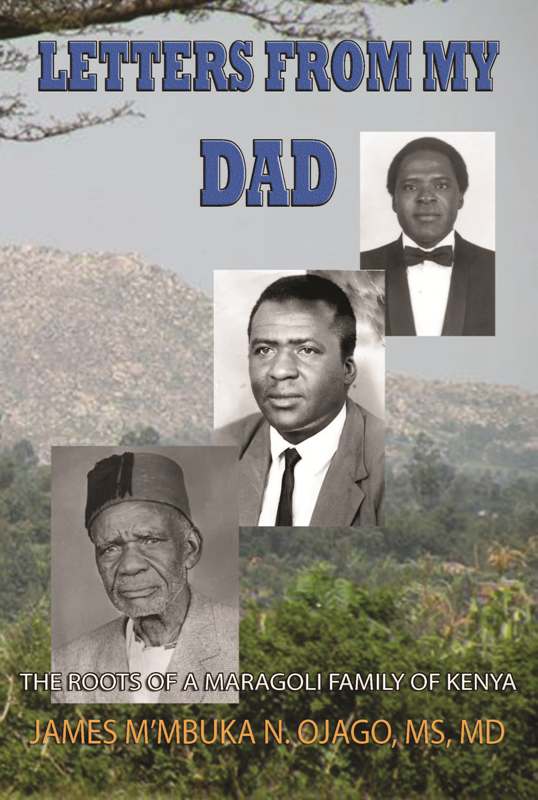

The picture of Maragoli Hills near Vihiga, on the Luanda to Majengo highway, the place where the Maragoli people first settled when they arrived in the area, forms the background of the cover of the book. The front cover carries images of the writer’s grandfather, father and himself, in that order.

Letters from My Dad: The Roots of a Maragoli Family of Kenya, that is available directly from the publisher, on amazon.com and electronically on nook.com, itunes.com and kindle.com, is published by Sarah Book Publishing (Sarahbookpublishing.com) of Texas, USA, in 2013.